12 01 11 Unpacking the Relational Universe

This summer we added a cat to our bioshelter family. The decisions to get a cat came as a result of a thriving shrew and vole population that loved our vegetables too much. I am sorry to say that we got very little broccoli or cauliflower this year, despite efforts to develop the soil and nurture the young plants. Once the voles found it, it was gone. We decided something had to be done, hence the cat.

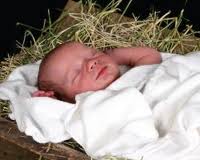

Latté came

As we live with our bioshelter home and its property, we have to ask what role it is that the human residents of this micro-environment are to play. Clearly, we have to exercise some management. We have to repair ventilation fans, or other mechanical components when they wear down; we have to care for the bacteria in our compost and in our water treatment system, we must decide how to grow vegetables that produce at least some food for us to eat (hence the cat); and we have to do all of this in a way that allow the various parts of the system to thrive well into the future. Our role is to manage things not just for ourselves, but for the whole system and all its members. Living in a bioshelter, we remain aware of our interdependence on all members of the system.

The human community must apply this same line of reasoning to the whole of our macro-environment, the planet earth. We currently have over seven billion people on the planet, all wanting to live well, and many believing that living well means over-consuming in the way that the Western civilizations have been doing for the past 150 years. I believe the human community needs to see itself as managers, or stewards of God’s creation, for the purpose of insuring that the whole ecosystem remains intact and the whole of life can thrive.

In short, we must manage ourselves. There is no reason to expect (or want) some other agency to manage us—by introducing some super-cat, for instance, to bring down the human population. We must pay attention and manage ourselves. As a Christian, I believe that this is the role that humans have always known themselves to play in the world. This is precisely what is meant when scriptures tell us we must exercise dominion in the world (Genesis 1:26); we must serve and protect the whole, and in so doing we care for ourselves.

Two weeks ago I interpreted the sentence “These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created… (KJV)” from Genesis 2:4 as a genealogy. I pointed out that the word “the generations of” (toh le doth really is only one word in Hebrew) is the same word that is often used to indicate genealogies in the Hebrew scriptures. (see Genesis 10:32 for Noah’s descendents, and elsewhere in Genesis). I suggested that we should therefore interpret the accounts of creation in Genesis as a description of humans-in-relationship with creation, much like relatives in a genealogy. I then promised to come back in a later blog and unpack my interpretation that this passage leads to a very relational view of creation and the place of humans within creation. After all, most English translations for Genesis 2:4 interpret the same sentence as “This is the account of the heavens and the earth when they were created…(NIV).” So let me go into this briefly.

First of all, the NIV translation of toh le doth as “This is the account of…” is not inaccurate. The root word roughly means “to bear” or “what follows out of,” and therefore is used for genealogies. However, this word also works well for a relational cultural view of describing history. Historical accounts are the stories of those events that unfold out of what happens before. There is a direct relational correlation between what is happening now to what came before, because there are only so many possibilities of what can immediately follow any given event. What happens now sets up the possibilities for what will happen next.

This insight leads to a real sense of the relatedness of all things that happen. In fact there is even a great sense of “generations” of happenings, because sometimes things seem to move along in one direction until some special event happens that turns everything in a new direction. Then a new generation of history continues to unfold, but down a new course, where things are different than before.

This understanding particularly guides the Book of Genesis. Genesis describes God’s activity in creating the heavens and earth, and then describes human activity within creation. There are consequences to that human activity, beginning with the entrance of sin into the universe, which changes the human condition. Then God acts again for the salvation of the humans, not destroying them because of the

sin, but providing a new and different path. And so it goes, throughout Genesis, with generation after generation of human activity, followed by moment after moment when God acts to change course, followed by more human activity, followed by more action on God’s part.

This very mindset that would use the phrase “the generations of,” relational language, to describe history is a mindset that knows the relatedness of all things, and the importance of remaining aware of the consequences of all actions. This kind of thinking knows that we humans

must make our decisions today with great care, even taking regard, as the Iroquois say, to the ramification of our decisions on those who will follow up to seven generations after us. It is therefore not inappropriate, when using the biblical revelation as our guide, to say that we must know ourselves as related to all creation and all of history. We must manage our own actions well, which requires considering our impact on our relatives, the other members of the natural environment.

Shrews and voles, of course, do not consider such things. They simply live. And when their numbers grow so large that they overtax their environment, they die off. Of course, in our bioshelter home, they are dying off for a different reason. We did not wait for them to overeat our vegetables and then die. We brought in a predator. We understood that the garden was not there just for them. It was there, primarily, to feed us. Since they could not manage their own population to leave enough for us, then we had to consider what we could do about it. That was, and is, our role as managers.

Now, we must manage ourselves.

Comments

Post a Comment